"Clothes make the woman but, more importantly, a woman makes the clothes." Travilla 1953

Throughout his film career, Travilla had dispensed fashion

advice in newspaper columns and fan magazine articles for publicity. In 1944, socialites,

studio wives, and actresses bought exclusive Travilla designs from Drew

Tetrick's Beverly Hills Rodeo Drive salon. A decade later, while still under contract to Fox, on

March 15, 1954, WWD announced that Travilla had become the designer for Harry

Finer, a manufacturer of women's suits ($110 to $135), beginning with their

Fall Collection. It noted his current Academy Award nomination in Costume

Design for the fashion-filled How to Marry a Millionaire (he lost to The

Robe.)

He may have lost out on another Oscar, but on April 6, he finally received his degree in Fashion Arts from Woodbury College. According to the Registrar's Office, "Some may participate in commencement ceremonies with degree requirement(s) pending, spend years working, and then come back because they realize they don’t have an awarded degree. When a student officially completes their last degree requirement, that is when their degree is awarded."

His first display ad in WWD debuted in the April 23 edition. It features a roughly drawn logo of his signature above the address with "Showings May 2-12. Reservations can be made by calling CRestview 5-9836." The logo would be the same one he used on the labels sewn into his fashions for several years.

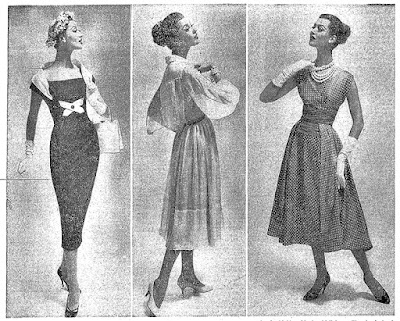

Travilla would recall just two years later, "I had eleven things in my first collection. Invited a few store owners in to see them. The orders came pouring in, and I was not prepared to fill them. But I did. And that's how the business got snowballing." Their first collection featured various one-piece day dresses in wool broadcloth or wool crepe. Soft draping gave the illusion of a weskit at the front or a U-shaped seam that gave shape to fluid back blousing. Slim dresses with a godet of fullness at one side or with crisp little pleats. Travilla transferred the silhouette to late-day dresses by changing wool to taffeta, peaugraine, or crepe. His formal gowns were a slim white silk crepe, shirred chiffon with trumpet hemline, and a satin and silk net ballgown. The outer coats featured shoe-button fastenings, and accessories included wide scarfs looped low at the back.

A model wearing the outfit for a September 1957 fashion show. Actress and Travilla customer Ann Sheridan is in the center with the designer at left.

The company quickly became successful. Sarris firmly believes because "Travilla's greatest talent was the ability to take any woman and make her look more beautiful. Not every star was a beauty, but he was able to enhance just the right characteristic...and make her look like one." Travilla said early on, "The ultimate for any designer is to achieve the perfect marriage of design and fabric."

Now titled Travilla Originals, the company moved from Santa Monica Boulevard to 853 North La Cienega Boulevard. A two-story building with 5200 square feet, the first floor became offices, a showroom, a fitting room, and the shipping department. Production was on the second floor with cutters, seamstresses, and storage.

In July 1957, he was showing in New York City, renting the

Venetian Suite at the Plaza Hotel. Described by fashion journalist

Aileen Ryan from the Milwaukee Journal as "Black-haired, of medium nature,

suntanned and boyish." He explained this was his fourth commercial

collection. The cohesive theme of the forty-two-piece collection was a forward

motion expressed through seaming and collars. Sizes ran from 8-18, but he told

Ryan, "I make all of my models in size 16. It's too easy to make an attractive

size 8. If I can do it in 16, the 8 will take care of itself."

No comments:

Post a Comment